2.

The Social and the Real

The Pennsylvania State University PressEdited by

Alejandro Anreus, Diana L. Linden,

and Jonathan Weinberg

Social and Political Commentary in Cuban Modernist Painting of the 1930s

In Havana, on 7 May 1927, Cuban art and progressive politics first joined forces, opening the way for a decade of close collaboration between artists and left-wing intellectuals. On that evening, the Primera Exposici6n de Arte Nuevo (First Exhibition of New Art), organized by the cultural magazine Revista de Avance, opened at the Association of Painters and Sculptors' salon, launching the modernist movement in Cuban art. Earlier that day, the members of the Grupo Minorista (Minority Group), then Cuba's intellectual vanguard, wrote and signed a political and cultural manifesto known as the Declaration of the Minority Group, made public in the exhibition.1 The advanced social program envisioned in the declaration and the painting in the exhibition of Arte Nuevo were supposed to complement each other as the conceptual and symbolic guideposts to both a better Cuban republic and a more autonomous Cuban art.

Another event on that fateful day in Havana signaled the challenge for Cuban progressive politics and art in the coming years. The headline news that morning announced the return of President Gerardo Machado from a "victorious"visit to the United States, during which he received the continued blessing of North American business and the State Department and millions of dollars in loans to prop up the Cuban economy. Emboldened by these and other developments, Machado suspended upcoming elections in 1928 and appointed himself president for a new six-year term. Together these events set the stage for a decade of political violence and social upheaval, strengthening the alliance of many modernist artists with left-wing intellectuals and activists.

This essay aims to expand the discourse on a significant but little studied aspect of Cuban modernist art-the relationships between modernist painting, left-wing ideology, and Cuban politics in the 1930s. I am particularly interested in revisiting a significant selection of forgotten murals and somewhat heller known easel paintings by Carlos Enriquez, Arîstides Fernandez, Antonio Gattorno, Alberto Peña (known as Peñita), and Marcelo Pogolotti, in exploring their original context and ideology, as well as their contribution to the intense cultural, social, and political debates in 1930s Cuba.2 These debates centered on issues of Cuban independence vis-a-vis the United States, solidarity with Latin America, social justice and equality, education for all, and renewed efforts to define a Cuban cultural identity.

Cuban Modernist Art and Leftist Ideologies

The period from 1928 to 1940, from The second and self-appointed term of Machado to the inauguration of the second constitution, was a tumultuou decade in Cuban history. Near civil war, revolution, and nationalism marked the decade, including its cultural productions. The Cuban economy, closely tied to that of the United States, also underwent a depression beginning in 1929. The price of Cuba's two main crops-sugar and tobacco-upon which the entire economy depended, suffered a sharp drop due to the worldwide depression and the United States'

(Cuba's dominant trading partner) legislation to protect its own markets. Unemployment soared and poverty was rampant, especially in the countryside. The political situation, affected by the economic depression, was just as harsh. The 1930s began with Machado's dictatorship (1928-33) and violent opposition to it from left and right, followed by a brief revolutionary government, the result of an unlikely coalition of a mutinous army and radical university students (September 1933-January 1934), and ended with another dictatorship, that of General Fulgencio Batista (1934-39), who ruled behind puppet presidents for the rest of that decade.

During the 1930s Cuban artists were divided into two main groups: academicians and modernists. This essay is concerned with the modernists, whose political views varied widely but tended toward the left. Modernism in Cuban art emerged in the late 1920s, the 1927 Primera Exposici6n de Arte Nuevo representing an important point of departure, and reached its first mature stage during the 1930s. This seminal modernist movement in Cuban art, today generally known as la vanguardia (the vanguard), or Grupo Moderno (Modern Group) was made up of a loose group of artists born at the turn of the century, about the time Cuba became a republic (1902). Most of them studied at Cuba's official art school, known as the Academy of San Alejandro (founded in 1818), and the majority finished their artistic education in Paris in the late 1920s and early 1930s. The artists I am concerned with in this group were sympathetic to left-wing ideologies and produced in different degrees a social and politically oriented art.

By those on "the left" I mean members of leftist organizations, from the radical Left Wing Student Organization to the more conservative Cuban Communist Party, as well as those, the majority of the artists, who had socialist or anarchist leanings but were not affiliated with any political party. As varied as the vanguardia painters were in social class, political views, and artistic affinities, a fairly cohesive "generational" social and political ideology took shape in the 1930s. This ideology can be roughly defined by collective statements that political activists wrote but that the artists also signed. In a few instances we also have the statements of individual artists. Of the collective statements, the most important are the 1927 Declaracion del Grupo Minorista and the 1935 manifesto of the Union de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios de Cuba (Union of Revolutionary Writers and Artists of Cuba, or UEARc).

For the revision of false and tired values

For vernacular art and, in general, for new art in its diverse manifestations

For the introduction and popularization in Cuba of the latest artistic and scientific doctrines, theories, and practices

For reform in the public education system ... and autonomy for universities

For the economic independence of Cuba and against Yankee imperialism

Against political dictatorship in the world, America, and Cuba

Against the excesses of [Cuba's] pseudodemocracy, the falsity of

[Cuba's] suffrage, and for the effective participation of the people in government

For the betterment of the Cuban farmer and worker

for Latin America cordiality and union.'

Although only two of the vanguardia painters, Eduardo Abela and Antonio Gattorno, signed the declaration, much of the politically oriented Cuban art of the following year -from illustrations in Revista de Avance to easel and mural paintings-was motivated by the issues proclaimed in the manifesto. The Cuban modernist painters were in favor of "the latest artistic ... doctrines, theories, and practices" and "vernacular art." The former meant nonacademic and nonnaturalistic art, from Post-Impressionism to Surrealism. The latter was evident in the self-conscious nationalism of their subject matter. And these artists were also against "Yankee imperialism" and "political dictatorship," and for the better- ment of Cuban farmers and workers. Cuban social and political art of the 1930s addressed diverse issues that often blurred the lines between the cultural and the political.

The UEARC was a short-lived organization of writers and artists that published its own manifesto in the newspaper La Palabra on 3 February 1935. This newspaper and its editor, Juan Marinello, were associated with the Cuban Communist Party and the manifesto was published a few months before the major labor strike of May 1935, which signaled the end of the most revolutionary tendencies within the reform movement that had begun in 1923. If the Declaraci6n de! Grupo Minorista announced the revolutionary tendencies within vanguardismo, the UEARC manifesto was its last hurrah. A more populist and radical document than the minorista declaration, it was dedicated to Ruben Martinez Villena, the recently deceased founder of the Grupo Minorista, who led the Communist Party at the time of his death. This manifesto read in part:

1. [We will] work to create a national art in its tone and accent, yet also universal and human, in tune with current cultural developments.

2. An art of these characteristics must forcefully unite with the aspirations of our popular masses, eternal repositories of nalional and human values.

3. [Create] a true, large-scale, and revolutionary art.

4. All work that expresses "that which is Cuban" has to carry the anguish throbbing in our people for a better world.

5. For Afro-Cuban art to have significance in Cuba it must rest on the social equality and dignity of the man of color and the end of his unjust oppression. 5

In strong language, in which the imperative "must" dominates, the UEARC document called for an art of strong social content and context, privileging the popular voice and the underdog in the symbolization of the nation. In contrast with the 1927 de laration, there was no emphasis on "the new" or "the latest" per se, yet the commitment to "current cultural developments" was clear. The reference to a "vernacular art" in the earlier document was supplemented in the 1935 manifesto by a more pecific and radical call for an art based on the aspirations of the popular masse . Surprisingly, the reference to "Yankee imperialism" in the 1927 document is conspicuously absent in the 1935, maybe because the hated interventionist Platt Amendment had been abrogated the year before.1' The emphasis on Afro Cubans rather than the generic peasant and worker may be a measure of the growing cultural and social space blacks were opening for themselves in Cuba. Finally, the call for a "true, large cale, and revolutionary art" probably referred to the example of Mexican muralism. The manifesto was signed by a relatively large group of vanguardia painter : Jorge Arche, Enriquez, Gatlorno, Amelia Pelaez, Penita, Domingo Ravenet, and Lorenzo Romero Arciaga. But not all of the signatories social activities and art supported the platform of the manifesto. Pelaez did not produce art of social commentary, much less political protest. Arche, Gattorno, Ravenel, and Romero-Arciaga ventured only lightly into social commentary in their art. Only Peñita and some of the work of Enriquez parallel the tone of the UEARC manifesto.

Toward a Public Art

The most public, socially oriented, and revolutionary art of Cuba in the 1930s took the form of murals, some of which never got past the concep tual stage, while others were later destroyed." From 1928 to 1937 group of modernist artists approached public institutions and state and municipal organization in Havana with plan for mural projects, most of which were ignored or abandoned.

The Mexican mural movement inspired Cuban muralism in the 1930s. Indeed, Cuba's strong cultural connections with Mexico go back to the Spanish Conquest. Spain's first three colonizing expeditions to Mexico ( 1517, 1518, and 1519) were launched from Cuba, and throughout the colonial period Havana was the port of call for all Spanish hips returning from Mexico. After Mexico declared its independence from Spain, many Cubans involved in their own liberation effort took temporary refuge in Mexico. By the early twentieth century, travel, trade, and cultural contact between Mexico City and Havana were extensive. In the realm of the visual arts, the Mexican muralist movement was well known and respected among arlisb and intellectuals. Two of the magazines associated with the Cuban vanguardia, Social and Revista de Avance, regularly published articles on contemporary Mexican art and cultures. These magazines helped to introduce the main figures of the mural isl movement, principally Diego Rivera, to Cuban audiences. Mexican publications such as El Machete, the official newspaper of Mexico's Artists' Union and, after 1924, of the Mexican Communist Party, also reached I Iavana. In addition, Cuban and Mexican artists traveled back and forth between the two countries. Emilio Amero and Carlos Merida, then a ·sislants of Rivera, visited Havana, where they exhibited their work, in the 1920s. In the following decade, such Cuban artists as Peiiita, Mariano Rodriguez, Cundo Bermudez, and Mario Carreno visited Mexico for the expres purpose of establishing direct contact with the Mexican muralists.

At its most concrete, the contact between the Cuban and the Mexican avant gardes in the 1920s and 1930s led many Cuban artists to advocate a socially oriented public art, preferably in fre co. In their repeated allempts to learn the fresco technique and to paint murals in public buildings, they were indebted to the Mexican example. To the extent that mural ism is an unhappy chapter of the story of Cuban art of the 1930s, however, the Mexican innuence remained, contrary lo expectations, limited in scope; for even vanguardia painters committed to making social and political art were highly sensitive to their own national, historical, and ociopolitical circumstances, which were quite different from those of Mexico.

As one of the first modernist mural painters, Antonio Galtorno is a good case study for both the accomplishments and the limitation of muralism in Havana of the late 1920s and early 1930s. A 1921 gradu-ate of the San Alejandro Academy, Gattorno spent the next several years studying painting in Italy and France. Nol a follower of the latest trends, he gravitated in Italy lo the art of the Quattrocento and in Paris to that of Paul Gauguin. From these model he developed his own primitivist vision of rural Cuba. Upon his return to Havana in 1927 he became active in such leftist groups as the Grupo Minorista, the UEARC, and the avant garde publication Revisla de Avance ( 1927-30). Galtorno's admira lion for fifteenth-century Italian art and contemporary Mexican mural painting made him favor muralism al that moment in his career. "Painting," he wrote, "was born to decorate the most important spaces of a building, not lo fill the corners of a room." 10

Antonio Gattorno, “Decorative Panel” for the Pedagogical

School of the University of Havana, c 1929 (media dimensions,

and whereabouts unknown)

The University of Havana awarded one of the few public mural commissions of the 1920s to Gattorno, for a "decorative panel" to be placed in its Pedagogical School. The painting represented a mother/teacher figure crowned by a laurel of banana tree leaves, reading informally to her students/children, as a farmer-father figure rides slowly by, all in the midst of a friendly and intimate landscape. Beneath the painting is written in bold letters Jose Marti's oft-quoted line on the value of education: "Trenches of ideas are worth more than trenches of stones," a fitting caption to Gattomo's idealized image of rural literacy (fig. 1 ). From the point of view of critical social commentary, Gattorno's mural is problematic in that it masks the fact of widespread rural illiteracy aJ that time. Rather than express the need for the "betterment of the Cuban farmer and worker" stated in the minoristas' declaration of the same year, which Gattorno signed, his painting suggests that all is well in the Cuban countryside. Gattorno's socialist views and his primitivist style were clearly at odds. He sympathized with the plight of the guajiro, or peasant, but represented him as living an Arcadian existence.

Gatlorno was a muralist in the sense of the scale, placement, and function of paintings such as the one discussed above, but his style remained an extension of his easel paintings, and in fact all of his recorded murals are oil on canvas. Thus far, there is no indication that he ever painted a fresco. The fact is that Cuba's official art school, San Alejandro, did not teach fresco painting, and there was no tradition in Cuba of the use of such a technique. Cuban mural paintings, from Nicolas de la Escalera in the eighteenth century to Armando Menocal in the 1920s, were all done on canvas and hung on walls or ceilings.

Some modernist artists sought again to initiate mural projects for public buildings in the immediate aftermath of Machado's over throw in August 1933. A group of eight artists and one cultural activist approached the government of Grau-Guiteras and proposed to "to paint the walls of public buildings with the atrocities of the Machado regime and the heroism of our people, the students, and other revolutionary sectors," an honor for which they would not "charge one cent."11 The signatories to this request were Eduardo Abela, Jose Manuel Acosta, Jorge Arche, Romero Arciaga, Gabriel Castano, Aristides Fernandez, Jorge Fernandez de Castro, Antonio Gattomo, and Jorge Hernandez Cardenas. 12 Officials never responded to the petition, probably because the Grau-Guiteras coalition had their hands full with revolutionizing Cuban politics and the economy in their brief hundred days in office. Nevertheless, one mural project and one mural dating to that propitious time are worth studying for the light they shed on Cuban muralism of the 1930s.

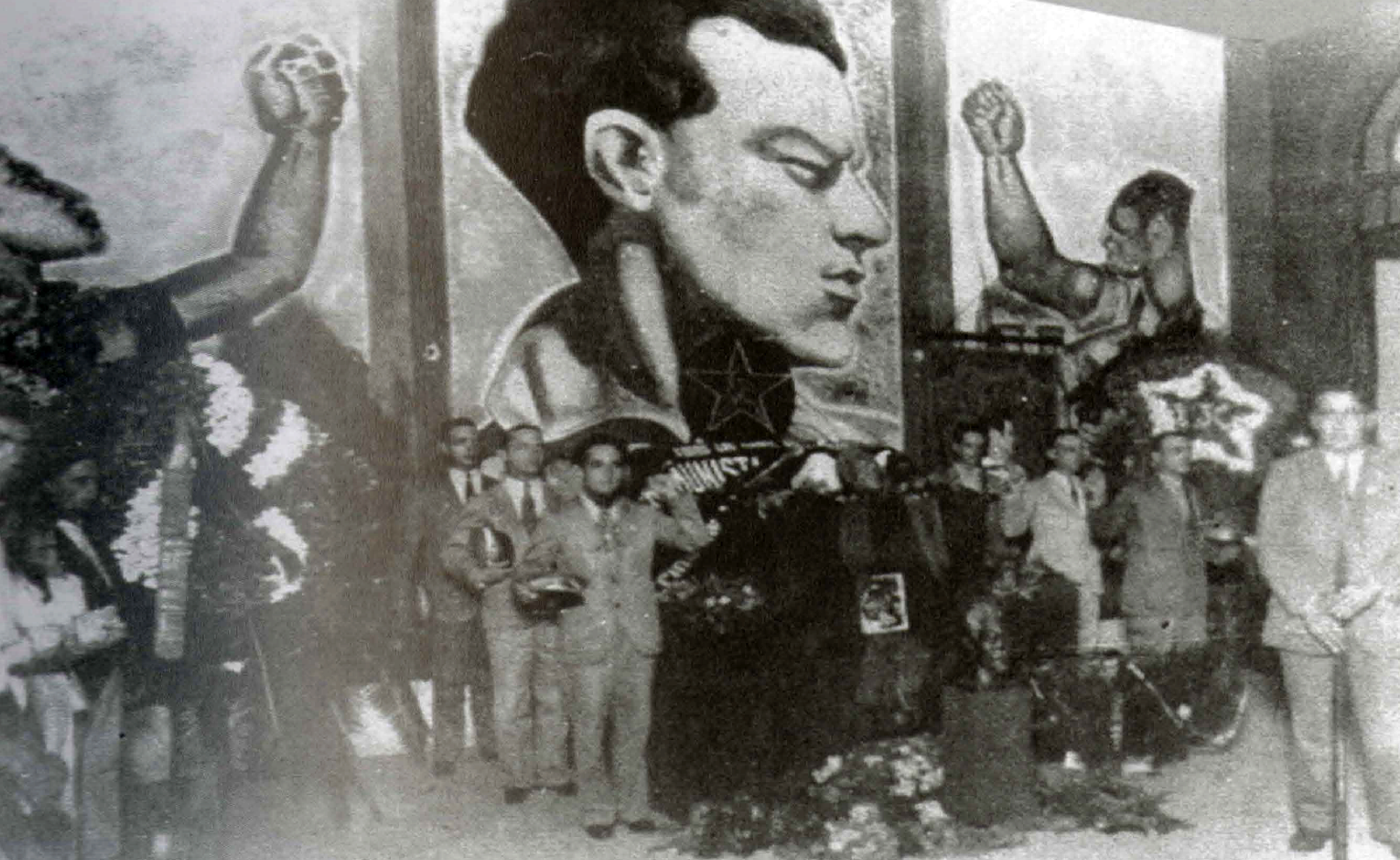

Gattorno and Castano collaborated with the Cuban Communist Party to paint a mural for Julio Antonio Mella's funeral, a politically charged event that took place in Havana on 28 September 1933, at the headquarters of the Anti-Imperialist League. 13 Mella was one of the most radical figures of the Cuban vanguardia generation, a leader of the university reform movement and one of the founders of the Cuban Communist Party. Imprisoned and then deported by Machado in 1926, Mella took refuge in Mexico, where he kept active as a writer and communist organizer until his assassination on 10 January 1929. 14 Soon after Machado's downfall, Mella's ashes were returned to Cuba for proper burial. A somewhat faded photo, the only record of the event and of Gattorno and Castano's lost mural, shows an urn flanked by an honor guard and behind it a high wall covered by a large painting (fig. 2). The mural features a large portrait of Mella's head in the center, flanked by students on one side and workers on the other, both shown with raised arms and closed fists. On stylistic grounds we may conclude that Gattorno painted the Mella portrait and Castano the lateral scenes. The artist based Mella's portrait on the mural on Tina Modotti's much-reproduced 1928 photograph of him. 15 Modotti, Mella's lover and companion at the time of his assassination, portrayed him as handsome, athletic, and intense. Her photograph shows an alert Mella, head in sharp profile, a solid neck, and a broad upper torso clothed in a worker's shirt. Gattorno amplified and simplified the image, turning it into a bold representation of a visionary leader. Most probably the context of the project and its patrons contributed to its unique qualities: the collaboration of two artists in the same painting, its specific communist subject, and its graphic visual language.

Antonio Gattorno and Gabriel Castaño mural for Julio Antonio Mella (1933)

Antonio Gattorno and Gabriel Castaño mural for Julio Antonio Mella (1933)(media and dimensions unknown; destroyed)

Like the revolution that inspired them, never realized, the mural projects of Aristides Fernandez, known only through preparatory sketches, are worth examining as an indication of the Cuban vanguardia's frustrations and muralism's potential in the early 1930s. Fernandez was a self-taught painter and writer of short stories who died at age thirty-four. He wrote most of his short stories between 1930 and 1933, and his artistic production dates to the last year of his iife. He spent part of that time trying in vain to learn the fresco technique and making bold sketches for planned murals. He seems to have been deeply moved by the revolution of 1933-34 and, with the help of the Mexican mural movement, tried to give artistic expres ion to that significant event. His friend and promoter, the poet and novelist rose Lezama Lima, wrote of Fernandez at this moment in his life: "[He] scratched the walls ... looking for the possibilities of our muralism, as the masses were jumping around the city. When the romantic struggle against the tyrant ended in August 1933, Aristides Fernandez believed that this political rift should have propelled its artistic parallel."16

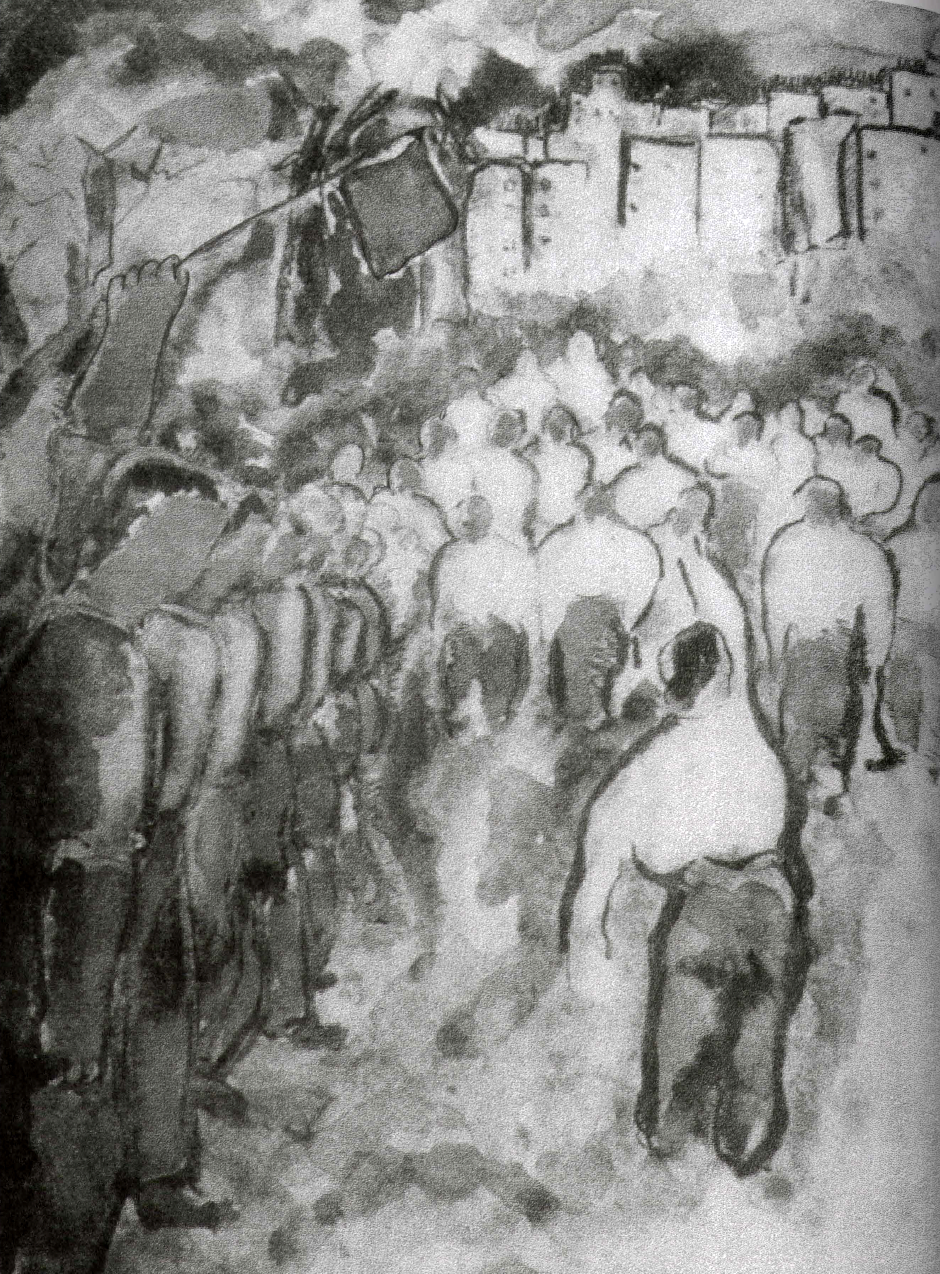

Aristides Fernandez, Manifestac1on con abanderado (Demonstrat,ons) (1933). ink and watercolor on paper, 472 x 366 mm. Museo Nacional de Bellas

Artes, Havana Cuba.

As one of the few artists of his generation who did not travel abroad, Fernandez made the most of his second-hand (photographic) knowledge of the paintings of Gauguin, Cezanne, Rivera, and (perhaps) Giotto. He shared with these arti ts an altraclion to pared-down form, strong, solid colors, and highly structured compositions. In regard lo con lent, the Manifestaciones sketches are about documenting and expressing the "heroism of our people" as they took Lo the streets in massive demonstrations against the Machado regime. In a more universal sense, they are about the modern phenomenon of marginalized mas es in an urban setting. As Enrique Carreno put it in his study of Fernandez's writing , "the author presents man as the masses, victim of social marginalization."18 Fernandez manifests this sense of the urban masses through the representation of anonymous figures and their decisive, desperate, and collective action.

After repeated attempts, beginning in 1928, a group of the vanguardia painters were finally given the opportunity to paint a series of murals in a public building in 1937. "On the initiative of Jose Luciano Franco and with the support of the mayor of Havana," read a note in the magazine Selecta, "a group of Cuban artists, members of the Society of Modern Artists, has filled with mural paintings the classrooms, dormitories, and salons of the secondary school Jose Miguel G6mez."19 This time the roster of artists included the most important names of the Cuban vanguardia: Carlos Enrfquez, Victor Manuel, Amelia Pelaez, and Fidelio Ponce. Absent were Aristides Fernandez, who had died in 1934, Antonio Gattorno, who left for New York around 19361 and Marcelo Pogolotti, who did not return from Paris until 1939.

By 1937 the modern isl movement had gained momentum in Havana, supported by a middle clas profe ional elite and by the Di rec ci6n de Cultura (Directory of Culture), a low budget agency of the Ministry of Education, recently created lo promote the arts. The edu cated elite-lawyers, doctors, architects, journalists, literary writers and poets provided venues for exhibition (such as the nonprofit women's organization, Lyceum), wrote for newspapers and magazines champion ing the modernist movement, and acquired artwork. al moderate price . The state, during the brief tenure of President Grau San Martin (Sep tember 1933-January 1934) and his revolutionary administration, began responding to long-standing demands by artists of all di ciplines who wanted o[ficial attention to and funding of the arts as part ol nation building. This renewed efforl oullasled the hundred day revolutionary government and led to the creation of the Direcci6n de Cultura a year later, and lo its sponsorship of the National Exhibitions of Painting and Sculpture. The modernist artists mentioned above figured prominently in the firsl and second of these exhibitions, held in 1935 and 1938. The modernist movement was also the subject of a major exhibition, with an ambitious catalog, organized by the office of the mayor of I lavana in 1937 and entitled the First Exhibition of Modern Art. That year leading modernist artists organized, after many failed attempts, a free art studio. During ils brief existence, the Studio Libre represented the first alter native to the monopoly of the Academy of San Alejandro in mallers of art education. With minimal state, municipal, and private support, the modernist movement in art had arrived in llavana's high culture by the micl-193os.

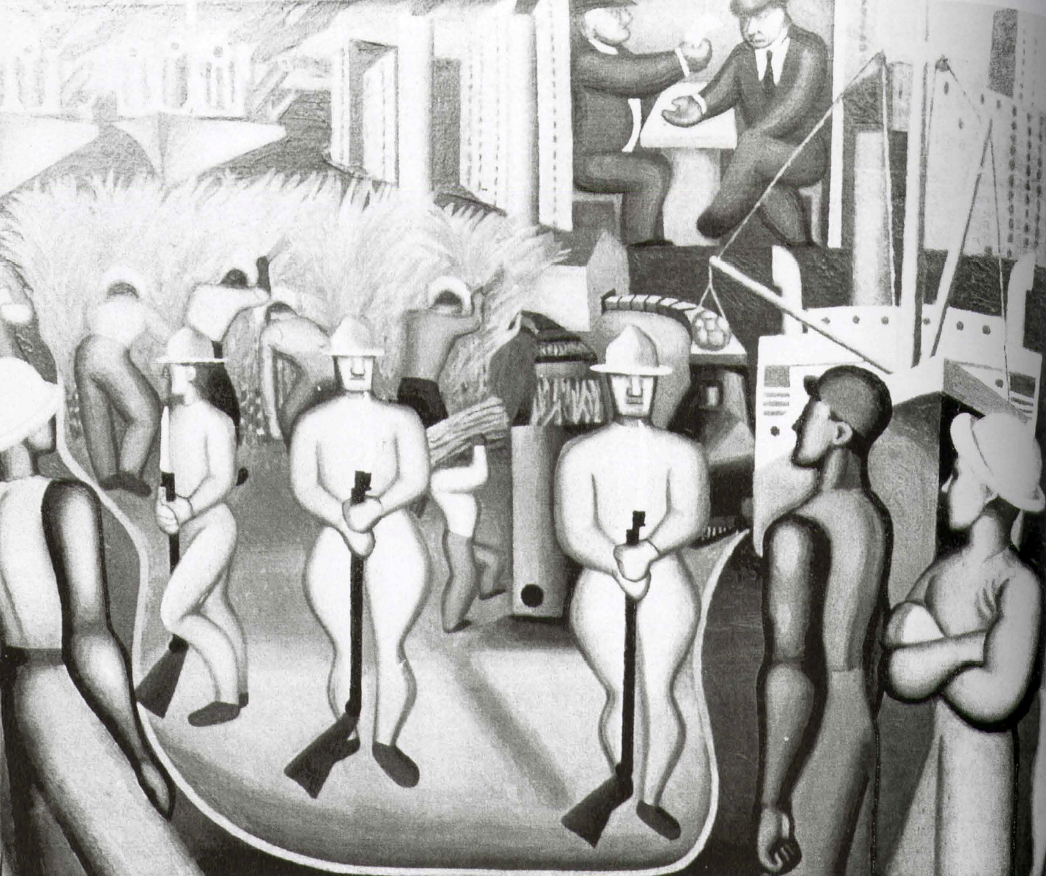

It is in this context that a group of modernist artists was commi sioned by the office of the mayor to do a mural project in a grand new public chool named for a veteran of the War of Independence and later president of Cuba, General Jose Miguel Gomez. The project had no overarching concept or theme, each artist selecting his or her own subject matter, technique, and dimensions. In personal styles that in theme and size were lose to their easel paintings, these artists dealt with various subjects-school, work, recreation, and history.20 Pei'iita's and Enrfquez's murals offered the strongest social commentary. Peiiila, an Afro Cuban from a working-class family, studied design at the School of Arts and Tracie in Havana and worked as a graphic design r for the municipal government. llis paintings represent lhe arti tic vanguardia al its closest to realism. Peiiita's arlislic production, limited in part because he died al age thirty-eight, included protest paintings aboul class, racial struggle, and the plight of the worker. Inspired by Mexican models, he developed a simplified naturalism to represent and agitate on behalf of rural and urban workers in Cuba. For his fresco at the Jose Miguel Gomez School, entitled La llamacla def ideal (The call of the ideal, 1937), he used a dry fresco technique with a synthetic resin base recommended by David Alfaro Siqueiros.11 The image (for the easel version, see fig. 4) center on a representation of Marti's head, providing the ideological framework for the struggling figures represented in the foreground. The poet, prolific journalist, and prime ideologist of the War of Independence of 1895 98 i shown a a collective and inspiring vision to Cuban workers men and women, black and white, urbanites and peasant -urging them to fight for their rights. The concept· of Cuban sovereignty and social justice for all, two major themes of Marti's political thought, were at the forefront of the vanguardia's political agenda, giving a nationalist slant to its leftist ideology. Like Gattorno and Castaño's Mella mural, Penita' composition is centered on a large, rhetorical, and inspiring portrait of a nationalist leader.

In contrasting to Penita's social realist approach, Carlos Enriquez's mural offers a complex visual language and subtle, if defiant, sosial content. Well born bohemian, painter, and writer, Enriquez is one of the most original pioneers of Cuban modernism. His foray into socially critical art began in the late 1920s with biting illustrations for Revista de Avance,22 followed in the mid-to-late 1930s by a few easel paintings of dramatic expresionism. The bulk of hi painting production from 1935 to 1940 con isted of a highly personal adaptation of modern European schools of art, from Expressionism to Cubism, and concept uch a prim itivism, which he used to depict the Cuban countryside. He called these productions, which included a strong dose of social criticism, romancero guajiro, or pea ant ballads. Enriquez's political ideology is complex, a combination of bohemian anarchism and independent left-wing views.

The bohemian side of his politics was defined by the artist himself in a 1936 article he wrote for the new paper El Pais, entitled "El arte puro como propaganda ha fracasado plenamente" (Art as pure propaganda has redundantly failed).21 "It is difficult to adju t art to a political mold," he wrote, "stereotyping a melodramatic theme until it become a poster, nullifying in this way art's creative purity and con tructive anarchism, the essence of all artistic work."14 Enriquez considered the emphais on illustrative content detrimental to art and, by implication, to whatever restricted artistic freedom, which he conflated with anarchism. For him it was the artist' life and attitude that held the potential for the creation of revolutionary art: "The artist must go through life perver e, destructor and creator at the same time, as a harmful entity, without du tic or obligations, without tradition and prejudice (as far as art i concerned), and thus produce true revolutionary work."25 Po tu ring aside, Enriquez associated with the Cuban left throughout his adult life and was close to Pogolotti, Martinez Villena, Marinello, Nicolas Guillen, and Agustin Guerra, among others. He also executed a number of paintings in the 1930s with strong social and political content. Enriquez combined a bohemian attitude toward Iife and art with leftist political views, a combination for which there is ample precedent in the history of modern art.

Alberto Peria El Llamado de/ Ideal (The Call of the Ideal) (1936), oil on canvas, 95 x 82 5 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba.

Carlos Enriquez La Invasion (The Invasion) (1937)

(fresco dimensions unknown; destroyed)

(fresco dimensions unknown; destroyed)

Enriquez, like Gattorno and Fernandez, had a strong interest in mural painting. Unlike them, he did learn the technique of fresco and used it in a number of mural paintings he did in Havana from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. His most ambitious was the fresco for the Jose Miguel Gomez School, entitled La Invasion (1937), which, according to a surviving photograph (fig. 5), measured forty feet and covered the long side of a rectangular dormitory.26 The destroyed fresco showed Enrfquez's mature expressionistic language of dynamic, exaggerated, and transparent representational forms, used to imagine and memorize a scene from the most significant campaign of the 1895-98 War of Independence. In a sweeping movement from left to right, the mambises, or independence fighters, are represented on horseback, machetes in hand, combating the Spanish forces, which are shown for the most part as entrenched riflemen at the bottom right of the painting. The crowded composition, with its forceful curving and diagonal lines, strongly expresses the subject of battle.

Although Enrfquez hardly dealt with historical subjects, he did a few very subjective paintings of figures and events from Cuba's Warof Independence, the most significant of which are El Rey de Los Campos de Cuba (The king of the Cuban fields, 1934), Dos Rios (Two rivers, 1939), and the mural in question. In the two easel paintings Enriquez concentrated on well-known, if very different, heroes of that war-Manuel Garcia and Jose Martf-with emphasis on the romantic notion of individual courage and action in the context of nationalism. La Invasion differs in that the nationalist cult of the hero is given a more collective slant. Its composition does not exalt the figure of a known leader but represents a group of evenly spaced anonymous fighters. On the social and political level, the significance of the painting's content is related

to Enriquez's, and his generation's, view of the War of [ndependence as a defining moment in Cuban history-and also as an incomplete project, given Cuba's neocolonial relationship with the United States after independence from Spain. In the context of Cuban history and the artist's leftist ideology, La Invasion can be read as an inspirational painting aimed at keeping the flame of Cuban sovereignty alive, after the debacle of the revolution of 1933 and the island's deepening economic and political dependence on the United States. All of the murals at the Jose Miguel Gomez School were later painted over because school officials considered their artistic form and social message subversive. More recently, all of these paintings, but Enr{quez's, have been restored.27

Among the vanguardia movement's contribution to Cuban art in the 1930s was its push for socially conscious public art, which was more or less achieved through murals. Vanguardia painters added the technique of fresco to the limited repertoire of painting techniques then practiced in Cuba and made a significant contribution to the development of publicly oriented art on a large scale. Owing to the lack of a strong muralist tradition in Cuba and to the absence of state support, mural painting in the 1930s was caught between promise and reality. Its production, thematic diversity, and social projection were limited but seminal.

Easel Painting, Social Commentary, and Protest

What the Cuban vanguardia could not fully accomplish in the field of mural painting it achieved in the more affordable medium of easel painting. Oriented more to elite consumption and with a long bourgeois history, easel painting is not the ideal medium for the creation of an" authentic, large-scale, and revolutionary art," as the UEARC manifesto put it, yet it served the Cuban vanguardia as the main vehicle for an art of social commentary and, at times, political protest. These easel paintings offer a more revealing sample of the vanguardia painters' range of artistic languages and socially oriented subject matter, as well as of their "true" audience-an elite within the Cuban middle class who befriended the artists, bought modestly from them, and organized exhibitions of their work with the help of the Lyceum (founded in 1929) and the Direccion de Cultura.

To the extent that those exhibitions can be reconstructed from catalogs and extant paintings in private and public collections, we know that there were a variety of artistic languages, more or less "revolutionary" in the context of Cuban art, and confluences in terms of subject matter. The same holds true for the more specifically socially oriented art within Cuban modernism. There are great distances between the gentle primitivism of Gattorno, the more crude primitivism of Fernandez, the social realism of Pefiita, the expressionism of Enriquez's paintings, and the purism of Marcelo Pogolotti, yet there are close affinities in their sociopolitical discourse. Certain popular and historical figures became dominant themes in imagining the nation at its most "authentic." The leading popular figures represented in modernist painting were the peasant, the Afro-Cuban, and the industrial worker, and the most often rendered historical character was Martî. The equation of the oppressed with the nation was one part of the leftist ideology of the 1930s in which these artists shared fully.28 Such a view of the nation was appropriated locally from Martî and internationally from European socialism and communism.

The plight of the peasant was a major theme in socially oriented Cuban art of the 1930s in that peasants made up the more numerous and exploited sector of the working class and at the same time symbolized the "authentically" Cuban because of their closeness to the land. Some of the most significant social paintings of the decade-in which women and the family are well represented-address this theme: Fernandez's Lafamilia se retrata (Family portrait, c. 1933), Pogolotti's Obreros y campesinos (Workers and peasants, c. 1933), and Enrîquez's Campesinos Jelices (Happy peasants, 1938) (fig. 6). These paintings are the first, in a tradition of representing the Cuban countryside that goes back to the nineteenth century, to present a problematic view of the life of peasants. The traditional picturesque view of the Cuban countryside is replaced in these paintings by images of poverty and work, presented by Enriquez as dire and harsh. They are pioneer images aimed at sensitizing Havana's white middle class to the conditions of the other Cuba-the island's interior.

The Cuban artist who most consistently dealt with the issue of class struggle, both urban and rural, from a Marxist point of view was Marcelo Pogolotti. A pioneer of the Cuban vanguardia in Havana in the late 1920s, he spent his brief mature phase, from 1930 to 1938, in Europe. His career cut short by blindne s, he returned to Havana in 1939 and became a successful writer. In Europe Pogolotti joined the Futurist movement while living in Turin, and after moving to Paris in 1934 he became a member of the Association des Escrivain et Artistes Revolutionnaires (Association of Revolutionary Writers and Artists).l9

By the mid-1930 Pogolotti had developed his own semi-abstract but figurative visual language of precise geometric forms and finished surfaces. His style, in contrast to that of his Cuban contemporaries, imparted a certain intellectual slant lo his protest paintings. Rather than invite sympathy for workers, it argues their case through the use of generic and hard-edged forms, and emphasizes the oppressive nature of industrial capitalism a a whole. Likewi e, in an essay entitled "De lo Social en el Arte" (About the social element in art), Pogolotli argued the case for socially oriented art: "No, social painting is not a futile dream. But to realize it, it is necessary to bring down all limitations and restrictions, doing away with prejudice against anecdote, symbolism, figuration, and literature and using the magnificent resources offered by modern painting."30 In his social paintings Pogololli achieved a synthesis of modernist artistic language, traditional literary subject, and Marxist ideology.

Although living in Europe, he kept in close contact with events in Cuba, and in 1933, al the height of the revolutionary surge, he painted one of the most direct and critical references to the Cuban situation of the era in Paisaje cubano (Cuban land cape, 1933) (fig. 7). This painting represents the main players in the Cuban sugar industry-greedy foreign businessmen in dark suits, the U.S. Navy's big guns, an omnipresent national army, and able productive workers (agrarian and industrial, black and white)-which he rendered in precise figurative forms arranged in a collage-like space. The image offers a cool but blunt condemnation of the exploitation of the sugar industry by foreign capital, U.S. gunboat diplomacy toward Cuba, and the plight of the rural and urban workers (represented by the ugarcane cutter and stevedore, respectively).

Another recurrent figure in Cuban social painting of the 1930s is the Afro-Cuban, which made only occasional appearances in the "peasant" and "worker" paintings. Although they had had a strong presence in Cuba since the early nineteenth century, when brought as slaves from West Africa to expand the sugar industry, and later played a prominent role in the Wars of Independence, Afro-Cubans as a group were the least able to enjoy the economic and political benefits of republican life. Black and mulatto Cubans remained among the poorest and least represented sectors of society well into the republican era. On the cultural front, while hegemony and prejudice prevented their heritage from entering high Cuban culture until the late 1920s. At that time the literary, musical, and artistic vanguard began to make Afro-Cuban popular culture vis- ible and audible to a white elite within the ruling class. Borrowing from popular culture, the Cuban modernist painters most often represented Afro-Cubans in the context of music, dance, and ritual, as seen in Eduardo Abela's El triunfo de la rumba (The triumph of the rumba, 1928) and Enriquez's Tocadores (Musicians, 1934). Although they presented a stereotypical view of Afro-Cubans, such images signaled the beginning of acceptance of African heritage as a bona fide and integral part of Cuban high culture. The mostly white middle-class vanguardia generation was the first to acknowledge and welcome the African contribution to Cuban life.

Carlos Enriquez, Campesinos Felices (Happy Peasants) (1938), oil on canvas,

122 x 89 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba

122 x 89 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba

Marcelo Pogolotti, Paisa1e Cubano (Cuban Landscape) (1933), oil on canvas 73 x 92.5 cm. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba

Finally, of all the leaders of the Wars of Independence fought by Cuba against Spain from 1868 to 1898, Marti slowly emerged as the foremost apologist for and symbol of that epic effort. The vanguardia writers in particular-Marinello and Jorge Mafiach, among others-researched and published significant texts on Martf beginning in the late 1920s. In the visual arts Martf was usually represented as an icon, as for instance in Peñita's aforementioned Llamada al ideal (c. 1937) and Jose Arche's Jose Marti ( 1943). In general there was a tendency to immortalize him as a man of thought rather than action, whose guiding ideas on Cuban nation building survived him. A significant exception is Enriquez's Dos Rios, which represents Marti's death on the battlefield and can be seen as a metaphor for the fate of the revolutionary movement by the late 1930s. Cuban modernist art of the 1930s, in tune with international developments in modernism, openly addressed social and political issues from a leftist point of view. In most cases, Cuban ocial and political art of the decade did not serve a direct propagandistic purpose on behalf of a specific political party but aimed to call attention to social issues of the day. For the most part the Cuban vanguardia painters went for oblique political commentary rather than outright declarations. At its most effective, Cuban social and political art of the 1930s represented workers and peasants, popular culture, and leftist politics that had been excluded from symbolic representation in Cuba. At its least effective, modernist political art in Cuba failed to claim permanent public space, an arena in which the Mexican mural movement had succeeded, and reached only a small segment of the population, in contrast to the Cuban poster movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s.