4.

Cuban Art and Identity

Ironside PressGeneral Editor: Lucinda H. Gedeon, Ph.D.

Representing Lo Cubano:

Cuban Painting 1900-1950

Cuban Painting 1900-1950

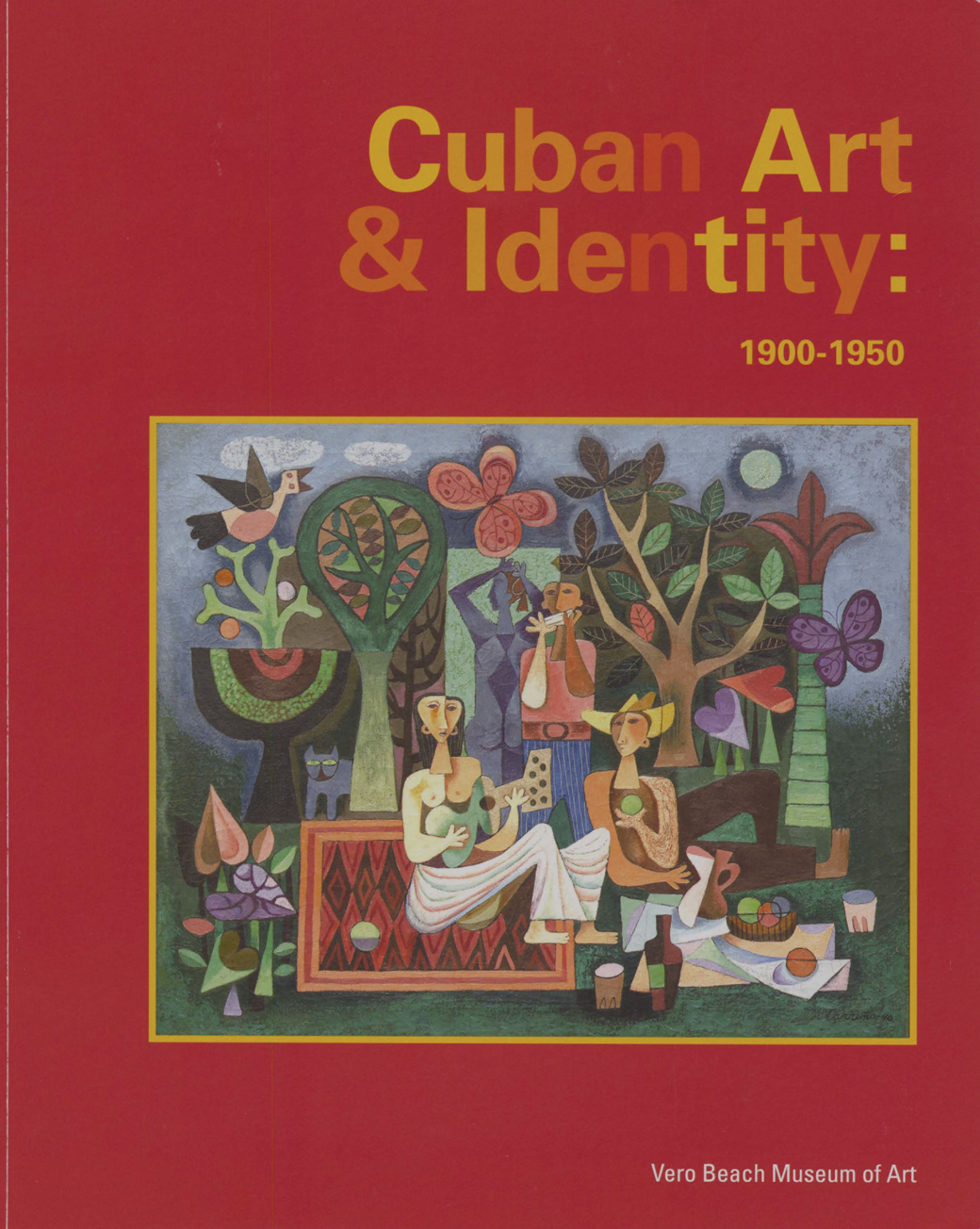

The aim of this exhibition is to examine Cuban painting of the first fifty years of the Republic with an emphasis on subject matter rather than style. It will explore four major themes found in traditionalist and modern painting: the Cuban countryside, Havana interiors, religious traditions, and music.

Traditionalist and Modern Painting

The term academic painting has been generally used to indicate certain Cuban art and artists of the Republican period. The term has been applied to those artists who studied and later taught at Havana's Fine Arts Academy, known as San Alejandro (founded in 1818), and who practiced styles that ranged from Romanticism and Realism to a mild form of Impressionism. In this essay I will use the term traditionalist rather than academic, which is a more descriptive and neutral term to classify their styles and narrative approach.1 The term modern is usually applied to artists who studied at, and then broke with, San Alejandro and adapted versions of Post-Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism and Surrealism. The term modem is also problematic for its implications go beyond stylistic preferences, suggesting a much larger socio-historical context. Herein the term modem specifically refers to a global modernist movement in the arts, in which Cuba participated, characterized by a self-conscious break with traditional art styles.2 Cuban modernist and traditionalist artists actually had a similar education to the extent that they studied at San Alejandro and then travelled to Europe to further their cultural and artistic experience. The more traditional ones continued their education in the Academia San Fernando in Madrid or the Scuola de Bellas Artes in Rome or Florence; those interested in modern art went to Paris.

Once back in Havana, Cuban artists exhibited in a slowly growing number of private and public venues throughout the city. The traditionalists gravitated towards Cfrculo de Bellas Artes (founded in 1916), the modem ones to the Lyceum (founded in 1929) and Galena del Prado ( 1942-43). Both groups participated in major state sponsored exhibitions, such as the National Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture held in 1935, 1938, and 1944, and in 300 Hundred Year.s- of Art in Cuba, in 1940. Some of these venues were exclusively open to modem artists: Exhibition of New Art in 1927 and the First Exhibition of Modern Art in 1937. A few artists, such as Ramon Loy, moved in both camps. In the 1920s and 1930s, newspapers and magazines began to publish articles on art written by journalists and literary writers. By the next decade art critics and historians, such as Luis de Soto y Sagarra, Guy Perez Cisneros and Jose Gomez Sicre, brought a more rigorous approach to writing about Cuban art. The modernists had close relationships with two progressive cultural magazines: Revista de Avance (1927-30), and Origenes (1944-1956). Exhibitions at Cfrculo de Bellas Artes, the bastion of traditionalist art, were announced and reviewed m magazines such as Bohemia and newspapers like El Diario de la Marina. 3

Actually, the boundaries between these more or less defined and antagonistic groups fade when looking at their paintings' subject matter. They both favored representing the Cuban countryside, the street life and interiors of Havana, Afro Cuban and Catholic religious traditions, and music. They do differ in their approach. Traditionalist artists focused on naturalism and narrative in their paintings. The modernist painters opted for expressionism or abstraction and a symbolic approach to the subject. Some in the modernist movement also introduced an art of social criticism, absent in traditionalist painting. On the other hand, traditionalist painters took on Cuban historical themes, not a favored subject of the modernist painters. One reason is that government commissions for public buildings calling for historical subjects, as in the case of the old Presidential Palace in Havana, went to traditionalist painters.

Leading Cuban Themes

In representing the Cuban countryside, traditionalist and modernist painters generally concentrated on the landscape and on the life of the peasant or guajiro(a). For the most part, the peasant and country life was romanticized as pastoral. The land itself, its flora, and rural traditions were seen as a major source of national ethos by both camps.

Contrasting with the images of Cuba showing the countryside as the repository of that which is authentically Cuban are those that represent the city of Havana as the epicenter of Cuban culture. Modernist and traditionalist artists painted the streets, architecture, and interiors of the capital. The carnival, processions, street vendors, views of narrow and populated streets in Old Havana, the city's "baroque" architecture, and still life of typical flora and fauna also became symbols not only of Havana, but of Cuba itself.

The Spanish conquistadores annihilated the indigenous Tainos and their culture, including their religious practices. They were not as successful with the Africans they later brought as slaves. Since at least the nineteenth century, syncretic religions of African and European beliefs developed in the island. European/Spanish, Yoruba, Congo, and Calabari religious traditions collided and blended in Cuba giving way to new religions such as Santerfa, Palo Monte and Abahwi. During colonial times there was a production of Catholic religious paintings for churches and wealthy patrons, but it never developed into a strong school or gave Cuba outstanding painters in that genre. In the Republican period there were a few painters, modernist and traditionalist, who represented religious images based on Catholicism. More painted poetic versions of Afro-Cuban religious figures and practices beginning in the late 1920s.

Given the prominent role of music in Cuban culture it is not surprising that it is a recurrent theme in painting of the early twentieth century. Cuban music, like most of the island's culture, began to develop in the 19th century while still under Spanish rule. By the 1920s there was a variety of popular music on the scene: Danzon, Son, and Rumba, among others. These musical forms combined European and African instruments and musical elements to create Cuban music. Music and dance were also major ingredients of Afro-Cuban religious practices. At times, the line between the visual representation of popular and religious music/dance is blurred.

The Cuban Countryside

Around the middle of the 19th century visiting artists, such as Frederic Miahle and Henry Cleenewerck, and a little later native ones, like the Chartrand brothers, began to represent the landscape of the island. Their placid landscapes took notice of certain emblematic trees, Royal Palms and Ceibas in particular, the verdant vegetation, and sunny days. The traditionalist painters of the twentieth century mostly followed in their footsteps.

Of the many traditionalist artists who emerged in the early 20th century, only two have received wide recognition: Leopoldo Romanach ( 1862-1951) and Armando Menocal (1863-1942). Romai'iach studied painting in Havana and then in Spain, Italy and France. Upon his return, he taught color theory at San Alejandro and developed a reputation as a charismatic and tolerant professor. Beginning in the 1920s Romai'iach painted a series of seascapes of the shorelines of Cuba's northern coast that are among his best works. These paintings and studies stand out for their loose execution, luminous colors, and freshness. An excellent example is Seascape, ca. 1930, included in this exhibition (Fig. 4). In this painting the tactile treatment of the sand and thick scrubs contrast with the windy clouded sky. Delicate and swift brush strokes animate the entire surface. Surprisingly few Cuban painters until recently acknowledged the sea. Menocal studied painting in Havana and Madrid and was an ardent admirer of Velazquez' optical realism. He executed historical scenes, particularly related to Cuba's War of Independence, in which he participated, and also portraits and landscapes. He was a professor of landscape painting at San Alejandro and, like Romanach, served as director of the school for a number of years. He brought to landscape painting a keen observation of Cuba's flora and light. His painting, Bridge of the Palm Train, Cristal River, ca. 1930 shows a tight naturalism with a modern view of the changing landscape of the island (Plate 30). In this sober look at the Cuban landscape, the salient feature is not the palm trees, or the quiet river, but a red, metal bridge. Interestingly, this traditionalist artist acknowledged the intrusion of modernity into the Cuban landscape, which paradoxically modernist painters mostly ignored.

Antonio Rodrfguez Morey ( 1874-1967) is an underrated landscape painter, who studied in Florence and Rome, taught at San Alejandro, and in 1918 became the Director of Cuba's National Museum of Fine Arts, with which he maintained a long, productive relationship. Unlike his professor at San Alejandro, the landscape painter Valentfn Sanz Carta, who was a naturalist, Rodrfguez Morey was a complete romantic. Included in this exhibition is a fine example of his misty-eyed landscapes, Cuban Landscape, 1913 (Plate 35), and a unique piece, Symphony in Green (fig. 5) The latter's bird's eye view of a creek, lack of a horizon line, infinite shades of green, and musical title was innovative for its time.

One of the outstanding Cuban landscape painters is Domingo Ramos ( 1894- 1956). He studied in San Alejandro, and in the 1910s at San Fernando in Madrid. Upon returning to Cuba in the 1920s he became a professor at his alma mater. Ramos introduced Poinciana trees, with their fiery red-orange flowers, into the representation of the Cuban landscape, where green and violet had dominated. He is best known for his numerous representations of the Vinales valley in western Cuba, one of the most spectacular natural environments in the island. His style fluctuated from naturalism to a highly personal version of impressionism as seen in his luminous Landscape with Royal Poinciana, 1930, and Landscape with Highlands, 1925, a view of the Vinales valley (Plates 53 and 52)

Many of the modernist artists also painted landscapes with an eye for lo cubano. Vfctor Manuel Carda ( 1897-1969) is a pioneer of Cuban modern art who studied with Romanach at San Alejandro and found his mature, formal language in Paris under the influence of Cezanne and Gauguin. He is known for images of melancholic, mixed-race women and landscapes. Like Ramos, Vfctor Manuel enjoyed painting Poinciana trees for the vibrant, reddish-orange color of the flowers. His landscapes usually include a river, Royal Palms and/or Poinciana trees, people at leisure, and their ancestral homes known as bohios. They offer a serene, sensual, and intimate view of the Cuban countryside as seen in Landscape with River, ca. 1940s (Plate 21).

On the other end of the spectrum from the peaceful landscapes of Vfctor Manuel are Carlos Enriquez' windswept views of the Cuban countryside. Enrfquez ( 1900- 1957) studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art for one semester in 1925, lived in New York from 1927 to 1930 with his wife Alice Neel, and developed the basis of his mature style while living in Paris and Madrid from 1930 to 1934. Using a unique style of transparent color forms, he painted equestrian bandit/heroes, the poorest of the guajiros, horses, nude women, portraits, and landscapes. As suggested, his landscapes evoke the strong winds of a subtropical island, ignored by most Cuban landscape painters, and on the more imaginative side, he eroticized the land, as seen in the representation of the hills in Landscape with Wild Horses, 1941 and the Breasts of Madruga, 1943 (Plates 17 and 19).

The Cuban landscape also served as backdrop and context for representations of the guajiro(a). A number of artists in the turbulent 1930s took a critical view of the miserable economic conditions of those who worked the land. This is particularly evident in paintings by Carlos Enrfquez, Alberto Pena, and Antonio Gattomo. Enrfquez' s Coal Oven of 193 7 is an outstanding example of social criticism pointing to hard labor among the neediest peasants (Fig.6). In this exhibition Enrfquez's Coal Oven offers a major contrast with the romanticized view of the guajiro seen in Menocal's Peasant Child, 1930s (Plate 29). In the latter the child figure stands tall, good looking, and although at work, has a dreamy expression. Enriquez not only represented the toughest views of poverty in the Cuban countryside, he also transformed rural histories and legends into powerful visual mythologies such as Creole Bandit, 1943 (Plate 18). ln this painting the theme of abduction and flight is given a mythological dimension by the fusion of the outlaw, the abducted female nude, and the horse into a hybrid mythical being. Pena, better known as Penita ( 1897-1938), studied in the School of Arts and Trade in Havana and did not travel abroad. He developed a personal style of simplified forms and dramatic gestures to criticize the dismal working conditions of the working poor. Penita often represented the worker in the act of rebelling, as seen in his large painting Cuba on the March, 193 6 (Plate 41). Antonio Gattorno (1904-1980) studied in San Alejandro and spent most of the 1920s in Italy and Paris, where he gravitated towards 15th century Renaissance painting and the style of Gauguin. In the 1930s he concentrated in the representation of guajiros, usually couples or a family, seen as poor, but dignified. Peasant with Plantains of 192 7 is an early and accomplished example of his exploration of the guajiro theme (Plate 24).

Of the second-generation modernist painters, Mariano Rodrfguez ( I 912-1990) and Mario Carreno ( 1913-1999) stand out for their interest in the representation of the Cuban countryside. One of the leading figures of the 1940s generation, Mariano (as he is known) studied painting in Mexico with Manuel Rodrfguez Lozano and upon his return to Havana in the late 1930s painted the guajiro with a critical view. One of his outstanding paintings of that period is The Thread, 1939, showing a monumental female figure sewing in a spare room with a view of the countryside seen through an open door (Plate 55). In the 1940s, he abandoned the ochre tonalities and social criticism for a rainbow of colors and jubilant expression of the countryside, as seen in two major paintings of that decade: The Rooster, 1941 and Woman with Rooster, 1943 (Plates 56 and 57).

Many of the Cuban themes derived from life in the countryside originated in the nineteenth century, such as the figure of the guajiro and his customs, one of which is a passion for roosters and cockfighting. Modernist and traditionalist painters did variations on the theme. Two outstanding and contrasting examples included in this exhibition are Jose A Bencomo Mena's (1890-1962) Keeper of the Roosters, 1934 (Fig. 7) and Mariano's Woman with Rooster. Bencomo Mena followed the usual educational experiences of Cuban painters. He studied drawing and painting in San Alejandro and then furthered his artistic growth in Europe. He spent eight years in Florence and when he returned to Havana in 1927 joined the faculty of San Alejandro. In the 1930s he developed a personal style, which combined elements of early Italian Renaissance painting and Spanish Realism. His interpretation of the guajiro and his rooster culture is at once traditional and uniquely sober and exalted. Mariano on the other hand broke with tradition in his Woman with Rooster by changing the gender of the protagonist and sensualizing the relationship to the rooster. Inspired perhaps by the myth of Leda and the Swan, he shows a female figure embracing and pecking a rooster. The rich palette and brilliant colors exude sensuality. Similarly, Mariano's Rooster is a happy expression of Cuban light, color, and in this case masculinity.

Carreno, another leading figure of the secondgeneration modernists, painted some of the most ambitious representations of the guajiro in three large and colorful Duco paintings of 1943. Carreno studied painting in Havana, Mexico, and Paris and with consummate ease burned through various formal languages in his long artistic career. In 1943, under the influence of David Alfaro Siqueiros and with memories of his previous neo-classical phase, he painted Fire in the Outbuildings (Plate 11 ), Sugar Cane Cutters, and The Afro-Cuban Dance (Fig.8). Using bold colors and dynamic compositions, the guajiro is represented respectively as family oriented, hard working, and sensually spiritual. This exhibition brings together for the first time since 1943 two of these paintings, Fire in the Outbuildings, and The Afro-Cuban Dance. In the former Carreno presents a heroic view of the Cuban peasant as seen in the robust figures of the father and mother saving their child from a fire. Two years earlier Carreno took on the representation of a greater destructive natural force, hurricanes, in a smaller, but striking painting entitled Tornado (Plate 12). Painted in an expressionistic child like manner, it is one of very few paintings on a major and frequent phenomenon in Cuba. The strongly traditional view of the Cuban countryside as passive and idyllic seems to have discouraged the acknowledgement of such a natural disturbing force.

Landscape and the figure of the guajiro(a) embody a major recurring theme in Cuban culture and the visual arts. The countryside, its typography, its people and their traditions have been primary signs of lo cubano since the mid-nineteenth century. Closeness to the soil, "ser de la tierra," was a major leitmotif of the criollismo movement of the 1920s and 1930s, with its emphasis on rural life as the authentic Cuba.

Havana Interiors

Still life has not been one of the painting genres most favored by Cuban artists. Yet in the early twentieth century, there were two painters who are best known for their still lifes: Juan Gil Carcfa (1876- 1932) and Amelia Pelaez ( 1896- I 968). Gil Garcfa was a Spaniard active in Cuba from the 1910s through his death. He painted mainly landscapes and still lifes of fruits or flowers in a traditionalist naturalistic style. His still life production is large and had tremendous commercial success in the 1920s and 1930s. Still Life with Fruit, 1932 is a prime example of his work in this genre with its abundance of ripe, fleshly fruits described in a crisp realistic style (Plate 20). Cuba is represented as a tropical cornucopia. Usually, as in this painting, Gil Carcfa placed the fruits on the ground, connecting them directly to the Cuban soil. In this respect, they can be studied more in the context of landscape painting than the more typical association of still life with home interiors and culture, which is the case with Amelia Pelaez.

One of the pioneers of Cuban modernism in the 193 Os, Pelaez studied at San Alejandro with Romanach and later at Fernand Leger's Academie Contemporaine with the Russian avant-garde artist Alexandra Exter. She spent seven productive years in Paris, ending with an exhibition at the Zak Callery in 1933. Pelaez synthesized elements from the art of Matisse and cubism with native motifs derived from colonial architectural ornamentation to develop a highly personal style. An important aspect of her flowers and fish still life is their presentation (vases and tablecloth) and their setting (Neo-colonial interiors), both of which refer to the traditional Ibero-Cuban homestead of an affluent and educated elite, to which she belonged. Included in this exhibition are three major still lifes by Pelaez: Fishes, 1943; Fruit Dish, 1947; and Still Life, 1949 (Plate 39, Fig.9, Plate 40). In these paintings, Pelaez's bold arabesque of black lines, stained-glass-like colors, and dynamic semi-abstract compositions represent her modern neo-baroque style at its best. Their content is also significant. The fish is one of her favorite motifs, partly signifying the abundance of Cuba's surrounding sea. It should also be noted that the fish has a long history in Europe as a sign of Christ and Christianity in general. Pelaez and her circle were Catholics and sensitive to that tradition. Fruits are also a recurrent motif in her still lifes, in which not unlike the work of Gil Carda, they signify a sense of place and natural plenty.

Pelaez' barroquismo, in its form and content, made an impact on the secondgeneration modernist painters like Cundo Bermudez (1914-2008). His Still Life with Fish, 1948 is an outstanding example of his "naive," fairly ornamental, and color saturated barroquismo of the 1940s (Plate 8). Also included in this exhibition is one of Bermudez's masterpieces, Barber Shop, 1942, where his neo-baroque visual language transforms an ordinary genre scene into a fanciful and hefty subject matter (Plate 5).

One important exception to the joyful colors and native oriented content of modern and traditionalist Cuban painting, especially in the 1940s, is the work of Fidelio Ponce de Leon (1896-1949). The ghostly image of Vase with Flowers, 1935, whispers rather than shouts (Plate 43). Its Franciscan simplicity of form and intense light, suggested by the extensive use of white paint, gives the image a mystical ascetic quality, far removed from his colleagues' more tangible and elated visions.

The most imaginative and recognized expression of the Interior theme in Cuban painting during this period is Rene Portocarrero's series of paintings entitled Interiores del Cerro, inspired by interiors from the Cerro neighborhood in Havana, where the artist grew up. Portocarrero ( 1912-1985), a mostly self taught artist and one of the leading figures of the second generation modernists, liked to work in series, explored a wide range of media and subject matter, and was a master colorist. His Interior de/ Cerro included in the exhibition is a prime example of barroquismo in Cuban painting of the 1940s, offering a profusion of fragmented and varied colored forms supported by a dense linear arabesque (Fig. 10) As in the case of Pelaez and Bermudez, Portocarrero's barroquismo makes reference to the Spanish heritage in Cuban culture through allusion to its colonial and neocolonial architecture and furnishings.

The Interior theme often included a female presence. The association of women with home life has a long history in Western art and is a major theme in Cuban art of the early twentieth century. A number of outstanding paintings in this exhibition fall into that theme: Leopoldo Romaiiach's ( 1862- 1951) Lady with Flowers, ca. 1915 (fig. 11), Pelaez's Woman, 1941-44, Mario Carreiio's Seamstress, 1943, Bermudez's Girl in Pink, 1943 and Wifredo Lam's (1902-1982) Seated Woman, 1955 (Plates 37, 10, 6, 28). Romanach's painting shows a distinguished lady, relaxed and pensive, in a sparse and dark interior. She tenderly holds a flower, which seems to have sparked her daydreaming. Lam, who in the early 1920s studied in San Alejandro under Romanach, painted an equally impressive female figure seated in a dark interior, but there the similarities end. Informed by Cubism and Surrealism, with which he came into contact in Paris of the late 1930s, Lam drew more than painted an alert and tense female presence, depicted in confident and graceful lines, contrasting long sweeping contours with delicate decorative passages. The other three paintings mentioned above have in common the I 940s appetite for color and ornament. Carreno' s colorful and inventive architectural props transform a seamstress' usually drab environment into a world of wonder and gives her humble work a degree of glamour. Pelaez melds her monumental figure with the background interior space. The lower arabesque, which includes her favorite fish motif, suggests an elegant article of clothing, whereas the top ceiling decoration acts as a kind of halo. The neo-baroque style and large scale format, like in the case of Carreno's Seamstress and Bermudez's Barber Shop, transforms an ordinary task, in this case supposedly preparing fish for a meal, into a remarkable event carried out by a majestic figure in a grand setting.

The paintings of interiors with still life and/or female figures in Cuban painting of the Republican period represent for the most part an urban cultural space of plentitude, sophistication, and contentment. In the case of those with female figures, the interior theme also suggests the confinement of women to domestic roles and home life as was generally the case in the early Republic.

Religious Traditions

Traditionalist and modernist artists painted personal interpretations of Catholic and Afro-Cuban religious figures and rituals. The rising interest in Afro-Cuban culture in the 1930s as seen in the Afrocubanismo movement in literature, music, and art resulted in more attention paid to Afro-Cuban religious themes than Catholic ones. Traditionalist artists such as Manuel Vega Lopez (1892-1954), Oscar Carda Rivera ( 1914-1971) and Manuel Mesa Hermida ( 1895-197 1) painted Catholic and/or Afro-Cuban religious subjects. Of the modernist artists, Antonio Gattorno, Aristides Fernandez, Mariano Rodrfguez, and especially Fidelio Ponce de Leon painted highly personal interpretations of Catholic iconography. Carlos Enrfquez, Roberto Diago, Mario Carreno and especially Wifredo Lam imagined an Afro-Cuban religious iconography. Rene Portocarrero drew from both traditions.

In this exhibition the presence of the Catholic tradition in early twentieth-century art begins with Jorge Arche's ( 1905-1956) Portrait of Mongsenior Angel Caztelu, 1937 (Plate 3). Caztelu was at the time a young priest, poet, and supporter of Cuban modern art. Gaztelu' s friendship with a number of artists led in one way or another to the creation of important, if few, Catholic themed paintings in Cuban modern art: Arfstides Fernandez's The Burial of Chnst, ca. 1933, Mariano Rodriguez's The Cruxifiction and The Resurrection, 1944, and Fidelio Ponce's St. Ignatius of Loyola, late 1930s (Plate 46). In his portraits, Arche used a clean, linear style adapted from 15th century Italian Renaissance painting, which in this case gives the figure of the Monsignor a sober religious aura. Contrasting with the calm regal figure of Caztelu is Bermudez's humble Red Monk, 1948 (Plate 7). In a restrained but vigorous expressionist style, he represented a well-built monk standing against an ambiguous painterly background. The allusion to Catholicism is merely in the title.

If nothing else, the paintings of Ponce and Lam are enough to make the poetic representation of religious subject matter an important theme in Cuban modern art. Ponce, who studied for two years at San Alejandro and never traveled abroad, painted a sizable and powerful body of medium sized oils based on Catholic themes: Christ, nuns, initiates and at least one saint. He bathed his subject in an intense light suggesting a mystical vision. This exhibition features Novice, 193 8 and Saint Ignatius of Loyola (fig.12, Plate 46). Novice is a daring study in white suggesting an ethereal spiritual being. It is one of Ponce's most radical paintings in its extensive and refined used of white. Saint Ignatius offers one of the most unique and imaginative interpretations of the founder of the Jesuit Order. The strong contrast of black and white, the slanting figure of the saint, and the surprising still life next to him makes this painting dramatic and unsettling.

Lam, Cuba's best-known artist, studied at San Alejandro and at Madrid's San Fernando academy of art. He lived in Spain for an extended period of time and in Paris for two intensive years between 1938 and 1940. There he befriended Picasso, Matisse, and Breton among other leading figures of European modern art. On his return to Cuba in 1941, he took on the subject of Afro-Cuban religious traditions from a poetic and symbolic point of view. Using the tools of cubism and surrealism, he represented the persistence of African beliefs in Cuba. Included in this exhibition are two major paintings, which represent two stages of his development during his most valued decade. Malembo, Cod of the Crossroads, 1943, shows an early stage of his interest in Afro-Cuban sacred figures and rituals, when he set deities and their action in an exuberant, sun bathed, tropical background (Plate 27). Later in the decade, he did a series of elegant black and white paintings, such as For Want of Day, 1945 in which the Afro-Cuban subject takes on a more mystical quality. Lam's epic canvases and forceful style gave his representation of Afro-Cuban religion and culture a new gravitas with an edge (Fig.6). One other important painting with an AfroCuban religious theme in this exhibition is Portocarrero's Sorcerer, 1945. In his signature neobaroque style the artist totally integrates dynamic figures with a dense plant background suggesting the metamorphosis of man and nature (Plate 51).

The representation of religious themes in early twentieth-century Cuban painting is relatively small, but significant. In the 1930s and 1940s Afro-Cuban religions and their expression in popular culture entered Cuban high art and reached an early peak in the work of Wifredo Lam. Paintings and sculpture inspired by Catholic religious figures and events had their day in the 1940s emanating from artists associated with the Origenes group. A decade earlier, however, Fidelio Ponce had already painted the most imaginative and moving interpretations of Catholic figures.

Music

Since the early twentieth-century popular music has been one of Cuba's major cultural exports and known far better than its literature and visual arts. The musical forms known as Rumba and Son were particularly popular in the 1920s and 1930s and inspired a number of painters. Among the modernist painters, Abela was one of the first to represent scenes of musicians and dancers performing popular music, such as Party in the Outbuildings, 1927 (Fig.14). In this early modernist painting, Abela was particularly effective in giving the sense of animated dance movements and music through the handling of color and lines. Vfctor Manuel painted a few but ambitious carnival scenes in the l 940s. The one in this exhibition, Carnival, shows a group of revelers, some couples, engaged in vigorous street dancing (Plate 23). Among the traditionalists, Oscar Carcfa Rivera was also attracted to carnival scenes, as seen in his large Carnival Street Dance, ca. 1940 (Plate 54). Using a representational approach, Carda Rivera concentrates on illustrating a custom rather expressing, as in the case of Vfctor Manuel, the rhythm and sensuality of Afro-Cuban popular music.

Carlos Enriquez's The Musicians, 1935 is an outstanding representation of a Son musical group of the 1930s, when this type of music was at its high point (Plate 15). He paints a group of Afro-Cubans playing bongos and guitar and singing and dancing. The expressionistic approach and the dynamic representation of the dancing figure suggest the music itself. Sanchez Araujo's ( 1887-1946) Black Musician (Plate 3) is a study for a section of a large painting entitled La Rumba of 1937. In a realistic style that contrasts with Enriquez, he also represented a convincing scene of a musician in action and the suggestion of drumming sounds.

One of the most impressive representations of the musical theme in Cuban modem painting is Carreno's The Afro-Cuban Dance, 1943 (Plate 9). This large painting offers a monumental expression of sacred Afro-Cuban dance and by extension, music. A costumed male is shown dancing with a semi-nude female in the countryside at night. The massive but dynamic figures, painted with bright colors, bold curves, and collage elements, create a strong sense of movement. The mood of the painting is earthy and mysterious at the same time.

In two important and contrasting paintings in this exhibition the piano takes center stage. This instrument was introduced to Cuba in the 1830s and its practice soon spread due to the formation of numerous music schools during the same decade. By the early twentieth century piano lessons were part of the education of middle and upper class Cuban women. Pelaez's Women Playing Piano, 1940s represents that tradition (Plate 36). In her various versions of the subject, sometimes showing a duo playing the instrument as in this case, the performance or lesson is an intimate and domestic affair, suggested by the closeness of the figure(s) to the picture plane and by the shallow home interior. On the other side of the spectrum, the piano is part of a popular music scene in Roberto Diago's (1920-1955) Woman at Piano, 1940s (Plate 14). He represents a nude Afro-Cuban woman wearing large earrings and playing the instrument in a pitch-black space. The extensive use of black in the background gives the painting an air of mystery, accentuated by the ambiguity of the scene itself. Is this a nightclub act? Black musicians working directly or indirectly for the tourist industry prevailed in Havana then as now.

Painters in the early Republican period introduced Afro-Cuban popular music into high art as an expression of lo cubano. They paid tribute to Cuba's most widely recognized artistic form, the traditionalists mostly concerned with representing the musicians, instruments and dancers, and the modernists with the expression of the music's insistent rhythm.

The general preoccupation seen in the art of the Americas between the World Wars with national ethos is mirrored in Cuban painting. Being a new Republic, the symbolization of a national cultural identity carried some urgency and intensity. As usual with nationalism, there is not one stable vision of the nation, but different competing views depending on class, race, gender, dominant region, and moment in time. In the process of imagining the nation, some saw Cuba's cultural essence in the Spanish heritage, others in Afro-Cuban popular culture, still others in the blend of the two. Likewise, some perceived the countryside as the face and repository of authentic Cuban culture, while others found it in the eclectic urbanism of Havana. In all, Cuban painting in the first fifty years of the Republic offers a fundamental and dynamic discourse on Cuban cultural identity(ies) in the making.